Performance Hints

This post will be about going through https://abseil.io/fast/hints.html#performance-hints, a blog post written by the power duo Jeff Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat who argubly made google to what it is today. This is a knowledge distillation from the both of them with many examples from the internal codebase. Hopefully I can a thing or two professionals who have worked in the industry longer than I have been alive

Reflection after reading this post

Start at Performance Hints to see me go through the post while I’m reading through it. This short section is my takeaways from reading it.

TLDR, this post is about why you should build such an intuition and showing many outcomes from snippets of experience.

I think the intro was very very well written and puts some key points about thinking about performance into perspective.

The early sections, especially in “The importance of thinking about performance” and “Estimation” provides small window into how to think about performance as a sort of life-style choice (ie, having a habit of incorporating performance before and while the project is going rather than after). The motivations for why one sometimes should think in such a manner varies, but the authors argue that down the line, you face consequences or even bigger time sinks that could have been solved in the first place (harder time spotting the issues due to complexity, time sink to communicate with people complaining about what you wrote, changing existing library for performance gains is hard, using expensive bandaids to solve performance issues).

Estimation has and always will be important. It’s one way to judge if your intuition is right or not (guess, run experiment, am i wrong). And most likely, for me, it’s wrong. One tricky thing to spot is if something sounds right, but is wrong. Another habit that is hard to get is the “am I wrong” part, where I get lost in the sauce of doing something and then say “I’m done and ok yeah let’s move on to the next thing” and not asking the question “was I wrong initially” to see where I went wrong in my estimations, which can trickle down to actually doing the thing properly. And I think this should apply generally to anything, but I haven’t written and measured it outside of the work I do.

Detailed example sections I find new to me and seemingly useful: “What to do when profiles are flat”, “Code size considerations”, “Parallelization and synchronization”, “CLs that demonstrate multiple techniques”.

Side notes (my thoughts)

One thing now I especially now to think about is cost associated with performance. People typically talk about running services at scale and how many machines are needed for X system to run properly, but I believe what is just as important to look at is the view of a single node and its resources. These resources are repeated and scaled too. The number of cores is now 64, 128 or 256, and don’t get me even started with GPU cores. How many GB/s of memory/disk can transfer within a node? Then any improvement in compute or transfer on a single node trickles a bit down to a cloud native setting and is most likely easier to profile and debug.

So…, ironically, although chips have gotten faster and faster and resoources are getting cheaper (memory, disk), and yet we still care about performance? Is it cost? Usability? Or do we face new applications that require more performance?

What about power? Power seemingly is becoming more and more of a concern with AI in the GPU/hardware space, which could result in errors on the chip. Or was it already? I mean the main costs after building the chips, racks and datacenters are power and maintainance. It seems like the only way performance can affect power consumption is inadvertently, either through eliminating or doing less work (basically improving the algorithm). And sometimes performance gains can increase the work done (more nodes could result in less latency). So the question I’m getting at is how do we factor in is how to lower power while keeping the throughput or latency steady (something like undervolting in the gamer space where users tweak their hot GPUs to run at a way lower power while keeping 95%+ of performance).

Performance Hints

The importance of thinking about performance

This section is the introduction. They both have added very insightful, yet succint sentences that makes me ponder much.

Knuth is often quoted out of context as saying premature optimization is the root of all evil. The full quote reads: “We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%.” This document is about that critical 3%, and a more compelling quote, again from Knuth, reads:

If you go to the link, Knuth actually luminates more on this “… pass up our opportunities in that critical 3 %. A good programmer will not be lulled into complacency by such reasoning, he will be wise to look carefully at the critical code; but only after that code has been identified. It is often a mistake to make a priori judgments about what parts of a program are really critical, since the universal experience of programmers who have been using measurement tools has been that their intuitive guesses fail. After working with such tools for seven years, I’ve become convinced that all compilers written from now on should be designed to provide all programmers with feedback indicating what parts of their programs are costing the most; indeed, this feedback should be supplied automatically unless it has been specificly turned off”

This was published on Decemeber 01, 1974. And yet hasn’t been solved. What makes me believe that AI will solve this if after 50+ years since this has been written that AI can? What makes this such a hard problem to solve?

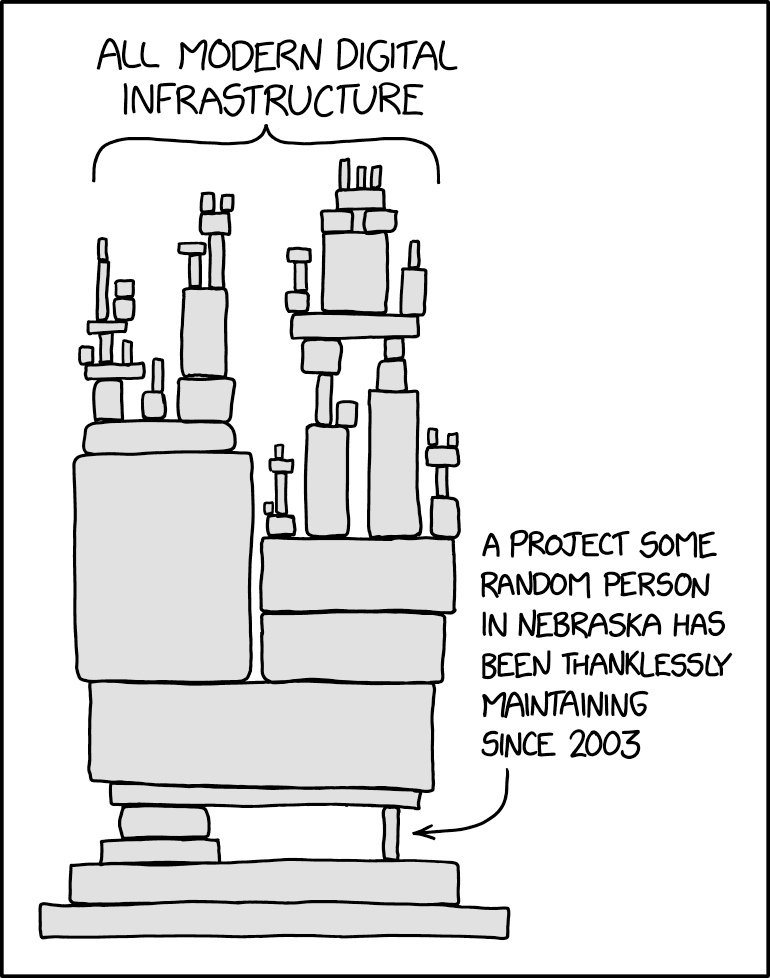

Is it “just” telling someone “hey buddy, the code written/generated here is slow?” and now tell the AI to fix it? And what makes me believe that AI will find that 3%? Or maybe that 3% doesn’t actually matter for most people, it just matters for critical pieces of code is written like postgres, mongodb? Or if you flip it, maybe the 3% matters a lot because it’s used by the 99% of people ~ xkcd image below:

Many people will say “let’s write down the code in as simple a way as possible and deal with performance later when we can profile”. However, this approach is often wrong:

When I first read this, I was like spot on. But doing this is difficult. How can you think of performance ahead of time? First, the question is does performance matter - always yes! it matters to some X degree, either cost, usability, etc. And second, what type of performance is needed and to what degree? Are we focused on latency for usability? reliability? cost? adability? and for each how much time do we pour and what is a good expected number to reach. these are some difficult questions to think about ahead of time without many years of experience, not just touching one project in depth, but many and each project with different goals and purposes.

The baseline of knowing this is napkin math. And I still need to work on that and integrate it programs I’m working on. And I believe that is true for some things outside of just computer science. If you’re putting money into say, a stock, ideally you have some idea of what’s going to happen and give an educated guess. Or maybe you need to measure if you’re going to traveling with multiple people, I don’t think yoloing the trip will make a majority of people happy in most cases.

If you disregard all performance concerns when developing a large system, you will end up with a flat profile where there are no obvious hotspots because performance is lost all over the place. It will be difficult to figure out how to get started on performance improvements.

This is very true. One thing touches another and another and propagates. Let’s say the problem is TCP window size

For example, if you’re serving a GET request in nodejs for a website and like wow, it’s taking 1-2s from US east to west. You start adding print lines to the code to get time measurements. Hmm it seems like this fetch from db is taking a while await db.query(...). maybe it’s the db. you change the query to something simple await db.query(SELECT ... COUNT 1) and then, oh it’s better. Then you could optimize that query and then bam, queries are ~500ms, so that’s like somewhat reasonable.

But maybe you dig a little differently (not necesarily deeper). You return some dummy result instead of the db query. Oh? it’s faster? Hmm. By stroke of messing around, you try a big dummy return and you see that it’s 1-2s. What’s happening? Ask AI, etc. maybe you get TCP window size. So it’s 15kb size intially for 1RTT and the data you’re sending is like 1MB-2MB. So you have to somehow compress your data (hopefully it works) or return less data.

Similiar to the gym, switching too many variables at once (like workouts) at once can make it difficult to pinpoint what’s going on.

If you are developing a library that will be used by other people, the people who will run into performance problems will be likely to be people who cannot easily make performance improvements (they will have to understand the details of code written by other people/teams, and have to negotiate with them about the importance of performance optimizations).

This is the other part I’m less experienced with. I think one can get experience seeing this by working in open source or big tech where people care/have an incentive to improve a project. I wonder why others cannot easily make the perf improvements with other’s library? Many people don’t have the time or reason to look deeper, which usually doesn’t give an obvious big net benefit (not to say that it gives a net benefit at all!)?

I guess the question is how can you make it usable? One obvious answer is feedback. But how do you get effective feedback? Is it just talking to people who complain about it not working and trying to decipher what that means?

A business will face this issue with people. People don’t care about what goes on in the product. They want it to work for their specific use case cause it’s easier (cost and time) than doing it themselves.

It is harder to make significant changes to a system when it is in heavy use.

Another part that I’m not familiar with. Clearly either big tech or open source again is where one can see that. I guess one thing that sticks out is that you have to accomdate existing users and people and try to convince them to switch. An example of this is the python2 to python3 switch. I was kind of mad that you needed to do print(...) instead of print ... because you need to type ( and ) parens and they were kinda hard to reach physically (having to press shift + 9) compared to space.

And yet I think, for most things, it most likely has to change at one point. Not many things in life don’t change.

For examples, many year friendships with people change typically one way or another.

It is also hard to tell if there are performance problems that can be solved easily and so we end up with potentially expensive solutions like over-replication or severe overprovisioning of a service to handle load problems.

Another area I’m not an expert in. One can guess and estimate issues, but honestly, it’s fucking hard. Real applications typically have explosions in usage typically at certain times and the let’s solve this for now by X and vibe it with things I know can be just patches and not solving the actual issue and maybe you actually spend more time than necessary to solve it or more money than necessary. But identifying whether to spend that time now or later is so difficult to tell.

Instead, we suggest that when writing code, try to choose the faster alternative if it does not impact readability/complexity of the code significantly.

Not sure what to expect, but I will revisit these 4 key points when I’m done going through the rest

Estimation

If you can develop an intuition for how much performance might matter in the code you are writing, you can make a more informed decision (e.g., how much extra complexity is warranted in the name of performance).

Oh man, the word intution. Ugh, it’s like the best word for what it describes, but it varies per person on how they learn and build an intuition.

Is it test code? If so, you need to worry mostly about the asymptotic complexity of your algorithms and data structures. (Aside: development cycle time matters, so avoid writing tests that take a long time to run.) Is it code specific to an application? If so, try to figure out how much performance matters for this piece of code. This is typically not very hard: just figuring out whether code is initialization/setup code vs. code that will end up on hot paths (e.g., processing every request in a service) is often sufficient Is it library code that will be used by many applications? In this case it is hard to tell how sensitive it might become. This is where it becomes especially important to follow some of the simple techniques described in this document. For example, if you need to store a vector that usually has a small number of elements, use an absl::InlinedVector instead of std::vector. Such techniques are not very hard to follow and don’t add any non-local complexity to the system. And if it turns out that the code you are writing does end up using significant resources, it will be higher performance from the start. And it will be easier to find the next thing to focus on when looking at a profile.

So my understanding is to think about what the type of work is being done for the application that you are building and to follow general good rules throughout building the project like you drinking X amount of water per day (drinking more is generally good for you for example)

You can do a slightly deeper analysis when picking between options with potentially different performance characteristics by relying on back of the envelope calculations. Such calculations can quickly give a very rough estimate of the performance of different alternatives, and the results can be used to discard some of the alternatives without having to implement them.

They finally mentioned it. Ok let’s see what has changed in the last ~20 years since Jeff first mentioned this.

Here is how such an estimation might work: Estimate how many low-level operations of various kinds are required, e.g., number of disk seeks, number of network round-trips, bytes transmitted etc. Multiply each kind of expensive operation with its rough cost, and add the results together. The preceding gives the cost of the system in terms of resource usage. If you are interested in latency, and if the system has any concurrency, some of the costs may overlap and you may have to do slightly more complicated analysis to estimate the latency.

Any transfer of movement of data should be measured, then multiply by the cost (time or $), and add to get total estimated result. The following table is what every one has seen.

L1 cache reference 0.5 ns

L2 cache reference 3 ns

Branch mispredict 5 ns

Mutex lock/unlock (uncontended) 15 ns

Main memory reference 50 ns

Compress 1K bytes with Snappy 1,000 ns

Read 4KB from SSD 20,000 ns

Round trip within same datacenter 50,000 ns

Read 1MB sequentially from memory 64,000 ns

Read 1MB over 100 Gbps network 100,000 ns

Read 1MB from SSD 1,000,000 ns

Disk seek 5,000,000 ns

Read 1MB sequentially from disk 10,000,000 ns

Send packet CA->Netherlands->CA 150,000,000 ns

You may find it useful to also track estimated costs for higher-level operations relevant to your system. E.g., you might want to know the rough cost of a point read from your SQL database, the latency of interacting with a Cloud service, or the time to render a simple HTML page. If you don’t know the relevant cost of different operations, you can’t do decent back-of-the-envelope calculations!

Yeah I understood this a bit better. It’s incredibly hard to track initially because it’s hard to know what’s important and I haven’t used it consistently daily/weekly, etc.

Example: Time to quicksort a billion 4 byte numbers

Before looking at the answer, I would like to ask myself where would this be used and where components are mainly involved and what is the majority of the cost(bottleneck)?

Maybe we have many time durations (say from multiple services) and would like to plot a histogram for a webUI query for latencies.

Components: memory, cpu. 1B * 4bytes = 4GB of data which is kinda tiny by today’s standard (one machine can handle it)

So let’s say it’s not on disk and in memory already. The quickest is if the data is already sorted and we’re only accessing each one and writing it back to another piece of memory. So 50ns * 1B * 2 (one for read and one for write), so 5s * 2 = 10s?

To be honest, it’s probably more, say all of the elements are unsorted, we would have to move all of them and then repeat on each subset as a slice like merge sort, and say without threading. So it would be like a infinite geometric series until converagance of 10s + 5s + 2.5s…, I had to search this up… s = a / (1 - r) which is 10s / (1 - 0.5) = 20s.

So between 10s and 20s would be my answer.

Memory bandwidth: the array occupies 4 GB (4 bytes per number times a billion numbers). Let’s assume ~16GB/s of memory bandwidth per core. That means each pass will take ~0.25s. N is ~2^30, so we will make ~30 passes, so the total cost of memory transfer will be ~7.5 seconds. Branch mispredictions: we will do a total of N*log(N) comparisons, i.e., ~30 billion comparisons. Let’s assume that half of them (i.e., 15 billion) are mispredicted. Multiplying by 5 ns per misprediction, we get a misprediction cost of 75 seconds. We assume for this analysis that correctly predicted branches are free. Adding up the previous numbers, we get an estimate of ~82.5 seconds.

My answer was way off. Let me actually look at the table and try to do in their style: 1. figure out the algorithm and the counts and 2. find the components involved.

Ok memory bandwidth is calculating the passes - 4GB/16GBs (read memory) * log(1B) (time per pass) = 0.25s * ~30 = 7.5s. Next is computation - branch prediction work = Nlog(N) compare = 1B*log(1B) = ~30B/2 = 15B. Then 15B * 5ns = 75s, which is surprising? I didn’t expect it to be compute bound.

Let’s assume we have a 32MB L3 cache, and that the cost of transferring data from L3 cache to the processor is negligible. The L3 cache can hold 2^23 numbers, and therefore the last 22 passes can operate on the data resident in the L3 cache (the 23rd last pass brings data into the L3 cache and the remaining passes operate on that data.) That cuts down the memory transfer cost to 2.5 seconds (10 memory transfers of 4GB at 16GB/s) instead of 7.5 seconds (30 memory transfers).

Wow… ok they talk about the caches here. 2^23 comes from… 2^20 (1MB) * 2^5 (32) / 2^2 (4 bytes per entry). So the last 22 can be loaded all in cache (N = 2^22)

Example: Time to generate a web page with 30 image thumbnails

Let’s compare two potential designs where the original images are stored on disk, and each image is approximately 1MB in size.

Two main compoennts: loading from disk and transferring data over the web. Total data: 30MB.

Disk: 30MB / 1GB/s = 0.03s. Web: log(30MB/1.5KB) * 150ms per roundtrip = 3 * 150ms = 450ms.

Read the contents of the 30 images serially and generate a thumbnail for each one. Each read takes one seek + one transfer, which adds up to 5ms for the seek, and 10ms for the transfer, which adds up to 30 images times 15ms per image, i.e., 450ms. Read in parallel, assuming the images are spread evenly across K disks. The previous resource usage estimate still holds, but latency will drop by roughly a factor of K, ignoring variance (e.g, we will sometimes get unlucky and one disk will have more than 1/Kth of the images we are reading). Therefore if we are running on a distributed filesystem with hundreds of disks, the expected latency will drop to ~15ms. Let’s consider a variant where all images are on a single SSD. This changes the sequential read performance to 20µs + 1ms per image, which adds up to ~30 ms overall.

Cool, I calculated per SSD and got it right. But, I guess realistically it would be the HDD version (say S3).

Measurement

The preceding section gives some tips about how to think about performance when writing code without worrying too much about how to measure the performance impact of your choices. However, before you actually start making improvements, or run into a tradeoff involving various things like performance, simplicity, etc. you will want to measure or estimate potential performance benefits. Being able to measure things effectively is the number one tool you’ll want to have in your arsenal when doing performance-related work.

I should really keep this in mind. Esimates before actually going to run it. The question is if it is even feasible.

As an aside, it’s worth pointing out that profiling code that you’re unfamiliar with can also be a good way of getting a general sense of the structure of the codebase and how it operates. Examining the source code of heavily involved routines in the dynamic call graph of a program can give you a high level sense of “what happens” when running the code, which can then build your own confidence in making performance-improving changes in slightly unfamiliar code.

Yes! I think just reading code gives one an idealistic view of the code. So much complexity happens behind the scenes. Is there lock contention? False sharing? Too much time spent allocating? Memory leaks? There are things to observe that is not so easily picked up by looking or stuffing the code into a llm.

Profiling tools and tips

If you can, write a microbenchmark that covers the code you are improving. Microbenchmarks improve turnaround time when making performance improvements, help verify the impact of performance improvements, and can help prevent future performance regressions. However microbenchmarks can have pitfalls that make them non-representative of full system performance.

Very true. It helps build understanding of individual components of the system to see where the full system has overhead.

What to do when profiles are flat

Find loops closer to the top of call stacks (flame graph view of a CPU profile can be helpful here). Potentially, the loop or the code it calls could be restructured to be more efficient. Some code that initially built a complicated graph structure incrementally by looping over nodes and edges of the input was changed to build the graph structure in one shot by passing it the entire input. This removed a bunch of internal checks that were happening per edge in the initial code.

Reduce loops into an array.

Take a step back and look for structural changes higher up in the call stacks instead of concentrating on micro-optimizations. The techniques listed under algorithmic improvements can be useful when doing this.

Algorithm level instead of micro optimizations

Look for overly general code. Replace it with a customized or lower-level implementation. E.g., if an application is repeatedly using a regular expression match where a simple prefix match would suffice, consider dropping the use of the regular expression.

Makes sense, seems micro optimization, I would be wary of this.

Attempt to reduce the number of allocations: get an allocation profile, and pick away at the highest contributor to the number of allocations. This will have two effects: (1) It will provide a direct reduction of the amount of time spent in the allocator (and garbage collector for GC-ed languages) (2) There will often be a reduction in cache misses since in a long running program using tcmalloc, every allocation tends to go to a different cache line.

Seen this happen SO many times. This takes up so many cycles, it’s actually frustrating to solve.

Gather other types of profiles, specially ones based on hardware performance counters. Such profiles may point out functions that are encountering a high cache miss rate. Techniques described in the profiling tools and tips section can be helpful.

Yes, but one needs to learn how to these performance counters at a system level and typically they are just samples (hard to pinpoint). I guess perf would help here with something like cache misses

API considerations

Widely used APIs come under heavy pressure to add features. Be careful when adding new features since these will constrain future implementations and increase cost unnecessarily for users who don’t need the new features. E.g., many C++ standard library containers promise iterator stability, which in typical implementations increases the number of allocations significantly, even though many users do not need pointer stability.

Make API as simple as possible, kind of like C i guess? But make the interface actually good.

Bulk APIs

Reduce the number of locks in memory allocations

template <typename T>

class ObjectStore {

public:

...

absl::Status DeleteRef(Ref);

template <typename T>

class ObjectStore {

public:

...

absl::Status DeleteRef(Ref);

// Delete many references. For each ref, if no other Refs point to the same

// object, the object will be deleted. Returns non-OK on any error.

absl::Status DeleteRefs(absl::Span<const Ref> refs);

...

template <typename T>

absl::Status ObjectStore<T>::DeleteRefs(absl::Span<const Ref> refs) {

util::Status result;

absl::MutexLock l(&mu_);

for (auto ref : refs) {

result.Update(DeleteRefLocked(ref));

}

return result;

View types

These types reduce copying, and allow callers to pick their own container types (e.g., one caller might use std::vector whereas another one uses absl::InlinedVector).

Yep! Been using this

For frequently called routines, sometimes it is useful to allow higher-level callers to pass in a data structure that they own or information that the called routine needs that the client already has. This can avoid the low-level routine being forced to allocate its own temporary data structure or recompute already-available information.

const WallTime now = WallTime_Now();

...

RPC_Stats::RecordRPC(stats_name, m);

const WallTime now = WallTime_Now();

...

RPC_Stats::RecordRPC(stats_name, m, now);

This makes sense

Thread-compatible vs. Thread-safe types

TransferPhase HitlessTransferPhase::get() const {

static CallsiteMetrics cm("HitlessTransferPhase::get");

MonitoredMutexLock l(&cm, &mutex_);

return phase_;

}

TransferPhase HitlessTransferPhase::get() const { return phase_; }

Have the user do the sync, makes sense for performance as the internal calls won’t be always locking

The most critical opportunities for performance improvements come from algorithmic improvements, e.g., turning an O(N²) algorithm to O(N lg(N)) or O(N), avoiding potentially exponential behavior, etc. These opportunities are rare in stable code, but are worth paying attention to when writing new code. A few examples that show such improvements to pre-existing code:

Rare in stable code! Man, they must have thought about most things.

Better memory representation

Careful consideration of memory footprint and cache footprint of important data structures can often yield big savings. The data structures below focus on supporting common operations by touching fewer cache lines. Care taken here can (a) avoid expensive cache misses (b) reduce memory bus traffic, which speeds up both the program in question and anything else running on the same machine

Yes, these are expensive resources on any machine.

Memory layout

Place hot read-only fields away from hot mutable fields so that writes to the mutable fields do not cause the read-only fields to be evicted from nearby caches.

Oh I get it, writes invalidate other core’s entries

Consider packing things into fewer bytes by using bit and byte-level encoding. This can be complicated, so only do this when the data under question is encapsulated inside a well-tested module, and the overall reduction of memory usage is significant. Furthermore, watch out for side effects like under-alignment of frequently used data, or more expensive code for accessing packed representations. Validate such changes using benchmarks.

Makes sense. Trade space for CPU like varint, etc.

Indices instead of pointers

On modern 64-bit machines, pointers take up 64 bits. If you have a pointer-rich data structure, you can easily chew up lots of memory with indirections of T*. Instead, consider using integer indices into an array T[] or other data structure. Not only will the references be smaller (if the number of indices is small enough to fit in 32 or fewer bits), but the storage for all the T[] elements will be contiguous, often leading to better cache locality.

Smaller indices. 4 bytes = 1billion indices already at 1/2 the storage cost

Avoid data structures that allocate a separate object per stored element (e.g., std::map, std::unordered_map in C++). Instead, consider types that use chunked or flat representations to store multiple elements in close proximity in memory (e.g., std::vector, absl::flat_hash_{map,set} in C++). Such types tend to have much better cache behavior. Furthermore, they encounter less allocator overhead.

Yes. But only in performant code. It’s sometimes tricky to have a flat representation, but flat hashmap/set is nice.

One useful technique is to partition elements into chunks where each chunk can hold a fixed number of elements. This technique can reduce the cache footprint of a data structure significantly while preserving good asymptotic behavior.

Yes! used in many implementations such as highly performant read/write queues.

Arenas

Arenas can help reduce memory allocation cost, but they also have the benefit of packing together independently allocated items next to each other, typically in fewer cache lines, and eliminating most destruction costs. They are likely most effective for complex data structures with many sub-objects. Consider providing an appropriate initial size for the arena since that can help reduce allocations. Caveat: it is easy to misuse arenas by putting too many short-lived objects in a long-lived arena, which can unnecessarily bloat memory footprint.

Basically allocate items ahead of time, but may not use the entire arena. It’s tricky to get right… very tricky… especially with estimatingg how big it should be.

Arrays instead of maps

If the domain of a map can be represented by a small integer or is an enum, or if the map will have very few elements, the map can sometimes be replaced by an array or a vector of some form.

const gtl::flat_map<int, int> payload_type_to_clock_frequency_;

// A map (implemented as a simple array) indexed by payload_type to clock freq

// for that paylaod type (or 0)

struct PayloadTypeToClockRateMap {

int map[128];

};

...

const PayloadTypeToClockRateMap payload_type_to_clock_frequency_;

Only used when key is index…

Bit vectors instead of sets

class ZoneSet: public dense_hash_set<ZoneId> {

public:

...

bool Contains(ZoneId zone) const {

return count(zone) > 0;

}

class ZoneSet {

...

// Returns true iff "zone" is contained in the set

bool ContainsZone(ZoneId zone) const {

return zone < b_.size() && b_.get_bit(zone);

}

...

private:

int size_; // Number of zones inserted

util::bitmap::InlinedBitVector<256> b_;

I’ve not actually used this before. Essentially a vector of bits instead of a set of values. I don’t use sets that often…

Reduce allocations

Newly-allocated objects may require expensive initialization and sometimes corresponding expensive destruction when no longer needed.

I see this time and time again

Every allocation tends to be on a new cache line and therefore data spread across many independent allocations will have a larger cache footprint than data spread across fewer allocations.

Yes. Batch your allocations (basically arena)

LiveTensor::LiveTensor(tf::Tensor t, std::shared_ptr<const DeviceInfo> dinfo,

bool is_batched)

: tensor(std::move(t)),

device_info(dinfo ? std::move(dinfo) : std::make_shared<DeviceInfo>()),

is_batched(is_batched) {

static const std::shared_ptr<DeviceInfo>& empty_device_info() {

static std::shared_ptr<DeviceInfo>* result =

new std::shared_ptr<DeviceInfo>(new DeviceInfo);

return *result;

}

LiveTensor::LiveTensor(tf::Tensor t, std::shared_ptr<const DeviceInfo> dinfo,

bool is_batched)

: tensor(std::move(t)), is_batched(is_batched) {

if (dinfo) {

device_info = std::move(dinfo);

} else {

device_info = empty_device_info();

}

Resize or reserve containers

for (int i = 0; i < ndocs-1; i++) {

uint32 delta;

ERRORCHECK(b->GetRice(rice_base, &delta));

docs_.push_back(DocId(my_shard_ + (base + delta) * num_shards_));

base = base + delta + 1;

}

docs_.push_back(last_docid_);

docs_.resize(ndocs);

DocId* docptr = &docs_[0];

for (int i = 0; i < ndocs-1; i++) {

uint32 delta;

ERRORCHECK(b.GetRice(rice_base, &delta));

*docptr = DocId(my_shard_ + (base + delta) * num_shards_);

docptr++;

base = base + delta + 1;

}

*docptr = last_docid_;

I actually do this a lot for my preallocated code for performance. Wow, I guess I do some things correctly

Avoid copying when possible

One of the most critical things to do (no work is better than having work)

return search_iterators::DocPLIteratorFactory::Create(opts);

return search_iterators::DocPLIteratorFactory::Create(std::move(opts));

auto iterator = absl::WrapUnique(sstable->GetIterator());

while (!iterator->done()) {

T profile;

if (!profile.ParseFromString(iterator->value_view())) {

return absl::InternalError(

"Failed to parse mem_block to specified profile type.");

}

...

iterator->Next();

}

auto iterator = absl::WrapUnique(sstable->GetIterator());

T profile;

while (!iterator->done()) {

if (!profile.ParseFromString(iterator->value_view())) {

return absl::InternalError(

"Failed to parse mem_block to specified profile type.");

}

...

iterator->Next();

}

Often, code is written to cover all cases, but some subset of the cases are much simpler and more common than others. E.g., vector::push_back usually has enough space for the new element, but contains code to resize the underlying storage when it does not. Some attention paid to the structure of code can help make the common simple case faster without hurting uncommon case performance significantly.

One has to understand the uncommon case underlying the API call. Say no error happened, we shouldn’t log at all.

void RPC_Stats_Measurement::operator+=(const RPC_Stats_Measurement& x) {

...

for (int i = 0; i < RPC::NUM_ERRORS; ++i) {

errors[i] += x.errors[i];

}

}

void RPC_Stats_Measurement::operator+=(const RPC_Stats_Measurement& x) {

...

if (x.any_errors_set) {

for (int i = 0; i < RPC::NUM_ERRORS; ++i) {

errors[i] += x.errors[i];

}

any_errors_set = true;

}

}

Preallocate 10 nodes not 200 for query handling in Google’s web server. A simple change that reduced web server’s CPU usage by 7.5%. Wow.

querytree.h

static const int kInitParseTreeSize = 200; // initial size of querynode pool

static const int kInitParseTreeSize = 10; // initial size of querynode pool

Specialize code

A particular performance-sensitive call-site may not need the full generality provided by a general-purpose library. Consider writing specialized code in such cases instead of calling the general-purpose code if it provides a performance improvement.

Interesting, I haven’t done this before. This should be put into very heavily usedd code.

p->type = MATCH_TYPE_REGEXP;

term.NonMetaPrefix().CopyToString(&p->prefix);

if (term.RegexpSuffix() == ".*") {

// Special case for a regexp that matches anything, so we can

// bypass RE2::FullMatch

p->type = MATCH_TYPE_PREFIX;

} else {

p->type = MATCH_TYPE_REGEXP;

Make the compiler’s job easier

The application programmer will often know more about the behavior of the system and can aid the compiler by rewriting the code to operate at a lower level. However, only do this when profiles show an issue since compilers will often get things right on their own. Looking at the generated assembly code for performance critical routines can help you understand if the compiler is “getting it right”. Pprof provides a very helpful display of source code interleaved with disassembly and annotated with performance data.

If you understand the code extremely well, you can get to this stage, OR use specific tool that shows the assembly (rare!)

Avoid functions calls in hot functions (allows the compiler to avoid frame setup costs). Move slow-path code into a separate tail-called function. Copy small amounts of data into local variables before heavy use. This can let the compiler assume there is no aliasing with other data, which may improve auto-vectorization and register allocation. Hand-unroll very hot loops.

void Key::InitSeps(const char* start) {

const char* base = &rep_[0];

const char* limit = base + rep_.size();

const char* s = start;

DCHECK_GE(s, base);

DCHECK_LT(s, limit);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

s = (const char*)memchr(s, '#', limit - s);

DCHECK(s != NULL);

seps_[i] = s - base;

s++;

}

}

inline const char* ScanBackwardsForSep(const char* base, const char* p) {

while (p >= base + 4) {

if (p[0] == '#') return p;

if (p[-1] == '#') return p-1;

if (p[-2] == '#') return p-2;

if (p[-3] == '#') return p-3;

p -= 4;

}

while (p >= base && *p != '#') p--;

return p;

}

void Key::InitSeps(const char* start) {

const char* base = &rep_[0];

const char* limit = base + rep_.size();

const char* s = start;

DCHECK_GE(s, base);

DCHECK_LT(s, limit);

// We go backwards from the end of the string, rather than forwards,

// since the directory name might be long and definitely doesn't contain

// any '#' characters.

const char* p = ScanBackwardsForSep(s, limit - 1);

DCHECK(*p == '#');

seps_[2] = p - base;

p--;

p = ScanBackwardsForSep(s, p);

DCHECK(*p == '#');

seps_[1] = p - base;

p--;

p = ScanBackwardsForSep(s, p);

DCHECK(*p == '#');

seps_[0] = p - base;

}

Reduce stats collection costs

Balance the utility of stats and other behavioral information about a system against the cost of maintaining that information. The extra information can often help people to understand and improve high-level behavior, but can also be costly to maintain.

Yes, I’ve seen this. How do you decide what to instrument essentially?

Part of changes that reduce time for setting an alarm from 771 ns to 271 ns.

selectserver.h

class SelectServer {

public:

...

protected:

...

scoped_ptr<MinuteTenMinuteHourStat> num_alarms_stat_;

...

scoped_ptr<MinuteTenMinuteHourStat> num_closures_stat_;

...

};

// Selectserver class

class SelectServer {

...

protected:

...

};

/selectserver.cc

void SelectServer::AddAlarmInternal(Alarmer* alarmer,

int offset_in_ms,

int id,

bool is_periodic) {

...

alarms_->insert(alarm);

num_alarms_stat_->IncBy(1);

...

}

void SelectServer::AddAlarmInternal(Alarmer* alarmer,

int offset_in_ms,

int id,

bool is_periodic) {

...

alarms_->Add(alarm);

...

}

/selectserver.cc

void SelectServer::RemoveAlarm(Alarmer* alarmer, int id) {

...

alarms_->erase(alarm);

num_alarms_stat_->IncBy(-1);

...

}

void SelectServer::RemoveAlarm(Alarmer* alarmer, int id) {

...

alarms_->Remove(alarm);

...

}

Often, stats or other properties can be maintained for a sample of the elements handled by the system (e.g., RPC requests, input records, users). Many subsystems use this approach (tcmalloc allocation tracking, /requestz status pages, Dapper samples).

When sampling, consider reducing the sampling rate when appropriate.

This change reduces the sampling rate from 1 in 10 to 1 in 32. Furthermore, we now keep execution time stats just for the sampled events and speed up sampling decisions by using a power of two modulus. This code is called on every packet in the Google Meet video conferencing system and needed performance work to keep up with capacity demands during the first part of the COVID outbreak as users rapidly migrated to doing more online meetings.

packet_executor.cc

class ScopedPerformanceMeasurement {

public:

explicit ScopedPerformanceMeasurement(PacketExecutor* packet_executor)

: packet_executor_(packet_executor),

tracer_(packet_executor->packet_executor_trace_threshold_,

kClosureTraceName) {

// ThreadCPUUsage is an expensive call. At the time of writing,

// it takes over 400ns, or roughly 30 times slower than absl::Now,

// so we sample only 10% of closures to keep the cost down.

if (packet_executor->closures_executed_ % 10 == 0) {

thread_cpu_usage_start_ = base::ThreadCPUUsage();

}

// Sample start time after potentially making the above expensive call,

// so as not to pollute wall time measurements.

run_start_time_ = absl::Now();

}

~ScopedPerformanceMeasurement() {

ScopedPerformanceMeasurement::ScopedPerformanceMeasurement(

PacketExecutor* packet_executor)

: packet_executor_(packet_executor),

tracer_(packet_executor->packet_executor_trace_threshold_,

kClosureTraceName) {

// ThreadCPUUsage is an expensive call. At the time of writing,

// it takes over 400ns, or roughly 30 times slower than absl::Now,

// so we sample only 1 in 32 closures to keep the cost down.

if (packet_executor->closures_executed_ % 32 == 0) {

thread_cpu_usage_start_ = base::ThreadCPUUsage();

}

// Sample start time after potentially making the above expensive call,

// so as not to pollute wall time measurements.

run_start_time_ = absl::Now();

}

packet_executor.cc

~ScopedPerformanceMeasurement() {

auto run_end_time = absl::Now();

auto run_duration = run_end_time - run_start_time_;

if (thread_cpu_usage_start_.has_value()) {

...

}

closure_execution_time->Record(absl::ToInt64Microseconds(run_duration));

ScopedPerformanceMeasurement::~ScopedPerformanceMeasurement() {

auto run_end_time = absl::Now();

auto run_duration = run_end_time - run_start_time_;

if (thread_cpu_usage_start_.has_value()) {

...

closure_execution_time->Record(absl::ToInt64Microseconds(run_duration));

}

Avoid logging on hot code paths

Logging statements can be costly, even if the logging-level for the statement doesn’t actually log anything. E.g., ABSL_VLOG’s implementation requires at least a load and a comparison, which may be a problem in hot code paths. In addition, the presence of the logging code may inhibit compiler optimizations. Consider dropping logging entirely from hot code paths.

image_similarity.cc

for (int j = 0; j < output_subimage_size_y; j++) {

int j1 = j - rad + output_to_integral_subimage_y;

int j2 = j1 + 2 * rad + 1;

// Create a pointer for this row's output, taking into account the offset

// to the full image.

double *image_diff_ptr = &(*image_diff)(j + min_j, min_i);

for (int i = 0; i < output_subimage_size_x; i++) {

...

if (VLOG_IS_ON(3)) {

...

}

...

}

}

const bool vlog_3 = DEBUG_MODE ? VLOG_IS_ON(3) : false;

for (int j = 0; j < output_subimage_size_y; j++) {

int j1 = j - rad + output_to_integral_subimage_y;

int j2 = j1 + 2 * rad + 1;

// Create a pointer for this row's output, taking into account the offset

// to the full image.

double *image_diff_ptr = &(*image_diff)(j + min_j, min_i);

for (int i = 0; i < output_subimage_size_x; i++) {

...

if (vlog_3) {

...

}

}

}

Run on (40 X 2801 MHz CPUs); 2016-05-16T15:55:32.250633072-07:00

CPU: Intel Ivybridge with HyperThreading (20 cores) dL1:32KB dL2:256KB dL3:25MB

Benchmark Base (ns) New (ns) Improvement

------------------------------------------------------------------

BM_NCCPerformance/16 29104 26372 +9.4%

BM_NCCPerformance/64 473235 425281 +10.1%

BM_NCCPerformance/512 30246238 27622009 +8.7%

BM_NCCPerformance/1k 125651445 113361991 +9.8%

BM_NCCLimitedBoundsPerformance/16 8314 7498 +9.8%

BM_NCCLimitedBoundsPerformance/64 143508 132202 +7.9%

BM_NCCLimitedBoundsPerformance/512 9335684 8477567 +9.2%

BM_NCCLimitedBoundsPerformance/1k 37223897 34201739 +8.1%

Code size considerations

Performance encompasses more than just runtime speed. Sometimes it is worth considering the effects of software choices on the size of generated code. Large code size means longer compile and link times, bloated binaries, more memory usage, more icache pressure, and other sometimes negative effects on microarchitectural structures like branch predictors, etc. Thinking about these issues is especially important when writing low-level library code that will be used in many places, or when writing templated code that you expect will be instantiated for many different types.

rn many map insertion calls in a row to initialize a hash table of emoji characters into a single bulk insert operation (188KB of text down to 360 bytes in library linked into many binaries). 😊

textfallback_init.h

inline void AddEmojiFallbacks(TextFallbackMap *map) {

(*map)[0xFE000] = &kFE000;

(*map)[0xFE001] = &kFE001;

(*map)[0xFE002] = &kFE002;

(*map)[0xFE003] = &kFE003;

(*map)[0xFE004] = &kFE004;

(*map)[0xFE005] = &kFE005;

...

(*map)[0xFEE7D] = &kFEE7D;

(*map)[0xFEEA0] = &kFEEA0;

(*map)[0xFE331] = &kFE331;

};

inline void AddEmojiFallbacks(TextFallbackMap *map) {

#define PAIR(x) {0x##x, &k##x}

// clang-format off

map->insert({

PAIR(FE000),

PAIR(FE001),

PAIR(FE002),

PAIR(FE003),

PAIR(FE004),

PAIR(FE005),

...

PAIR(FEE7D),

PAIR(FEEA0),

PAIR(FE331)});

// clang-format on

#undef PAIR

};

Parallelization and synchronization

Modern machines have many cores, and they are often underutilized. Expensive work may therefore be completed faster by parallelizing it. The most common approach is to process different items in parallel and combine the results when done. Typically, the items are first partitioned into batches to avoid paying the cost of running something in parallel per item.

Four-way parallelization improves the rate of encoding tokens by ~3.6x.

blocked-token-coder.cc

MutexLock l(&encoder_threads_lock);

if (encoder_threads == NULL) {

encoder_threads = new ThreadPool(NumCPUs());

encoder_threads->SetStackSize(262144);

encoder_threads->StartWorkers();

}

encoder_threads->Add

(NewCallback(this,

&BlockedTokenEncoder::EncodeRegionInThread,

region_tokens, N, region,

stats,

controller_->GetClosureWithCost

(NewCallback(&DummyCallback), N)));

The effect on system performance should be measured carefully – if spare CPU is not available, or if memory bandwidth is saturated, parallelization may not help, or may even hurt.

This is the caveat. It’s hard to guage this for every type of machine there is.

Amortize lock acquisition

Avoid fine-grained locking to reduce the cost of Mutex operations in hot paths. Caveat: this should only be done if the change does not increase lock contention.

Interesting. Yes, if there is another thread accessing it, it could theorically be faster (say some section isn’t using actually the shared variable)

// Acquire lock once to free entire tree of query nodes, rather than reacquiring lock for every node in tree.

// Pool of query nodes

ThreadSafeFreeList<MustangQuery> pool_(256);

...

void MustangQuery::Release(MustangQuery* node) {

if (node == NULL)

return;

for (int i=0; i < node->children_->size(); ++i)

Release((*node->children_)[i]);

node->children_->clear();

pool_.Delete(node);

}

// Pool of query nodes

Mutex pool_lock_;

FreeList<MustangQuery> pool_(256);

...

void MustangQuery::Release(MustangQuery* node) {

if (node == NULL)

return;

MutexLock l(&pool_lock_);

ReleaseLocked(node);

}

void MustangQuery::ReleaseLocked(MustangQuery* node) {

#ifndef NDEBUG

pool_lock_.AssertHeld();

#endif

if (node == NULL)

return;

for (int i=0; i < node->children_->size(); ++i)

ReleaseLocked((*node->children_)[i]);

node->children_->clear();

pool_.Delete(node);

}

Keep critical sections short

Avoid expensive work inside critical sections. In particular, watch out for innocuous looking code that might be doing RPCs or accessing files.

Basically minimize critical sections, but in addition, try to find these critical sections that have high ROI.

Avoid RPC while holding Mutex.

trainer.cc

{

// Notify the parameter server that we are starting.

MutexLock l(&lock_);

model_ = model;

MaybeRecordProgress(last_global_step_);

}

bool should_start_record_progress = false;

int64 step_for_progress = -1;

{

// Notify the parameter server that we are starting.

MutexLock l(&lock_);

model_ = model;

should_start_record_progress = ShouldStartRecordProgress();

step_for_progress = last_global_step_;

}

if (should_start_record_progress) {

StartRecordProgress(step_for_progress);

}

Reduce contention by sharding

Sometimes a data structure protected by a Mutex that is exhibiting high contention can be safely split into multiple shards, each shard with its own Mutex. (Note: this requires that there are no cross-shard invariants between the different shards.)

This just means that the underlying elements can be processed in parallel, but the global object cannot be accessed during this time. I didn’t realize you just could initialize multiple copies.

class ShardedLRUCache : public Cache {

private:

LRUCache shard_[kNumShards];

port::Mutex id_mutex_;

uint64_t last_id_;

static inline uint32_t HashSlice(const Slice& s) {

return Hash(s.data(), s.size(), 0);

}

static uint32_t Shard(uint32_t hash) {

return hash >> (32 - kNumShardBits);

}

...

virtual Handle* Lookup(const Slice& key) {

const uint32_t hash = HashSlice(key);

return shard_[Shard(hash)].Lookup(key, hash);

}

Be careful with the information used for shard selection. If, for example, you use some bits of a hash value for shard selection and then those same bits end up being used again later, the latter use may perform poorly since it sees a skewed distribution of hash values.

For sharding, equal distribution is always important. Nothing should be overloaded.

This CL partitions the ActiveCallMap into 64 shards. Each shard is protected by a separate mutex. A given transaction will be mapped to exactly one shard. A new interface LockedShard(tid) is added for accessing the ActiveCallMap for a transaction in a thread-safe manner. Example usage:

transaction_manager.cc

{

absl::MutexLock l(&active_calls_in_mu_);

delayed_locks_timer_ring_.Add(delayed_locks_flush_time_ms, tid);

}

{

ActiveCalls::LockedShard shard(active_calls_in_, tid);

shard.delayed_locks_timer_ring().Add(delayed_locks_flush_time_ms, tid);

}

The results show a 69% reduction in overall wall-clock time when running the benchmark with 8192 fibers

Reduce false sharing

If different threads access different mutable data, consider placing the different data items on different cache lines, e.g., in C++ using the alignas directive. However, these directives are easy to misuse and may increase object sizes significantly, so make sure performance measurements justify their use.

Trade size for performance… How do you even identify such a thing

histogram.h

HistogramOptions options_;

...

internal::HistogramBoundaries *boundaries_;

...

std::vector<double> buckets_;

double min_; // Minimum.

double max_; // Maximum.

double count_; // Total count of occurrences.

double sum_; // Sum of values.

double sum_of_squares_; // Sum of squares of values.

...

RegisterVariableExporter *exporter_;

HistogramOptions options_;

...

internal::HistogramBoundaries *boundaries_;

...

RegisterVariableExporter *exporter_;

...

// Place the following fields in a dedicated cacheline as they are frequently

// mutated, so we can avoid potential false sharing.

...

#ifndef SWIG

alignas(ABSL_CACHELINE_SIZE)

#endif

std::vector<double> buckets_;

double min_; // Minimum.

double max_; // Maximum.

double count_; // Total count of occurrences.

double sum_; // Sum of values.

double sum_of_squares_; // Sum of squares of values.

Reduce frequency of context switches

Process small work items inline instead of on device thread pool.

hard to see this without a tracer

Consider lock-free approaches

Sometimes lock-free data structures can make a difference over more conventional mutex-protected data structures. However, direct atomic variable manipulation can be dangerous. Prefer higher-level abstractions.

Extremely hard to debug and catch issues with. I don’t have expertise in this.

Protocol Buffer advice

I think this section is rather huge and for a good reason. Messages are one of the foundational building blocks of any distributed system and optimizing a small percentage will have high yields. This section is for good practices which can be applied to any message protocol.

What I mostly got from this section are that you need to see the generated serialization code and its overhead for serialization/deserialization and find the best practices to reduce the serialization/deserialization overhead (either by editing the proto file or by editing c++, by adding arenas).

C++-Specific advice

absl::flat_hash_map (and set). This is generall true for almost all standard libraries in C++ except a very small subset (like std::vector).

absl::InlinedVector stores a small number of elements inline (configurable via the second template argument). This enables small vectors up to this number of elements to generally have better cache efficiency and also to avoid allocating a backing store array at all when the number of elements is small.

This is probably just allocating on the stack. it’s nice, similiar to llvm::vector

gtl::vector32

Saves space by using a customized vector type that only supports sizes that fit in 32 bits.

Simple type change saves ~8TiB of memory in Spanner.

table_ply.h

class TablePly {

...

// Returns the set of data columns stored in this file for this table.

const std::vector<FamilyId>& modified_data_columns() const {

return modified_data_columns_;

}

...

private:

...

std::vector<FamilyId> modified_data_columns_; // Data columns in the table.

#include "util/gtl/vector32.h"

...

// Returns the set of data columns stored in this file for this table.

absl::Span<const FamilyId> modified_data_columns() const {

return modified_data_columns_;

}

...

...

// Data columns in the table.

gtl::vector32<FamilyId> modified_data_columns_;

This is very cool. I guess the data type won’t align up to 64bits, so you can cut it in half.

Bulk operations

As per usual, bulk computation is the answer since memory is the bottleneck…

Introduced a GroupVarInt format that encodes/decodes groups of 4 variable-length integers at a time in 5-17 bytes, rather than one integer at a time. Decoding one group of 4 integers in the new format takes ~1/3rd the time of decoding 4 individually varint-encoded integers.

groupvarint.cc

const char* DecodeGroupVar(const char* p, int N, uint32* dest) {

assert(groupvar_initialized);

assert(N % 4 == 0);

while (N) {

uint8 tag = *p;

p++;

uint8* lenptr = &groupvar_table[tag].length[0];

#define GET_NEXT \

do { \

uint8 len = *lenptr; \

*dest = UNALIGNED_LOAD32(p) & groupvar_mask[len]; \

dest++; \

p += len; \

lenptr++; \

} while (0)

GET_NEXT;

GET_NEXT;

GET_NEXT;

GET_NEXT;

#undef GET_NEXT

N -= 4;

}

return p;

}

CLs that demonstrate multiple techniques

This section is on seeing how a combination of techniques can be used to optimize a small part of a program and what to expect to the overall program.

For example, one speeds up GPU allocator by 40% using less bytes, caching aligning, caching and commenting out logging results in 2.9% speedup in end to end

Speed up low level logging in Google Meet application code.

This was changing logging state from vector to static array of size 4, resulting in 50% boost for logging, which might be pretty common call

I think all of these require very deep insights into what the program is doing and where the program is spending its time.

We found a number of performance issues when planning a switch from on-disk to in-memory index serving in 2001. This change fixed many of these problems and took us from 150 to over 500 in-memory queries per second (for a 2 GB in-memory index on dual processor Pentium III machine).

This is back in the day. Most likely applies still to personally written code, but doesn’t apply nearly as much these days as most people know the general optimizations and search was just becoming avaliable!

Further reading

Understanding Software Dynamics by Richard L. Sites. Covers expert methods and advanced tools for diagnosing and fixing performance problems.

Good book.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: